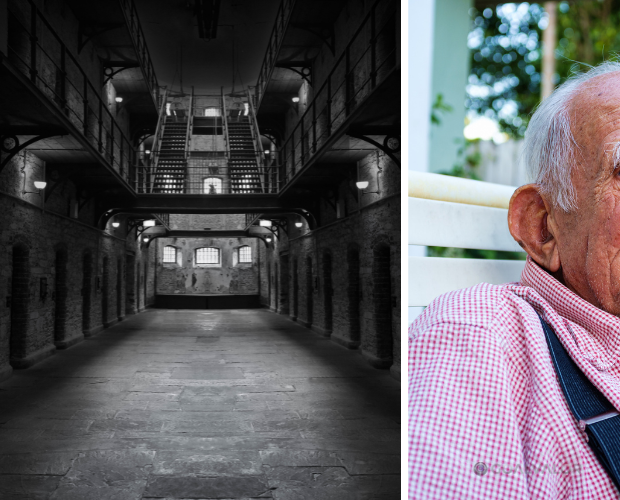

In an age where relationships are increasingly built through digital connections, the case of an 82-year-old French woman who chose to move to Ivory Coast to live with a man 54 years her junior, whom she met online, raises complex and unprecedented questions. Behind a personal decision that defies social norms lies a fragile balance between self-determination, potential emotional abuse, and institutional ineffectiveness.

The secondary protagonist is Xavier, the woman’s 61-year-old son, who has been appealing to French and international authorities for months. Although barely covered in the media, the situation highlights a tension between individual rights and the protection of vulnerable adults in non-European contexts.

According to the son’s account, his widowed mother—who suffers from health and mobility issues—met a 28-year-old man online. After a period of virtual contact, their relationship intensified, and she decided to leave Normandy and travel to Abidjan, Ivory Coast’s economic capital. Since then, she has sent sporadic updates: smiling but visibly weakened photos, confused stories about fainting and memory lapses, and declarations of affection toward her partner.

According to the son’s account, his widowed mother—who suffers from health and mobility issues—met a 28-year-old man online.

The legal ambivalence of individual freedom in old age

The core legal issue—often overlooked by moral interpretations—is that of decision-making autonomy. Marie-José, the woman in question, is not under legal guardianship, nor has she been deemed unfit to manage her affairs. She retains full legal capacity. This legal standing prevents French authorities or diplomats from taking coercive action, even when signs of manipulation or financial exploitation are present.

According to Xavier, two investigations have already been closed for lack of evidence. His mother’s pension—around €3,000 a month—is regularly transferred to foreign accounts. In a matter of months, the estimated loss, including savings, exceeds €100,000. Yet under current laws, no action can be taken unless the individual directly involved files a complaint. Marie-José, however, continues to affirm her right to choose: “I’m in love, I’m an adult, I have the right to be happy.”

The case exposes a legal gap in addressing relationships with asymmetrical dynamics, especially when they unfold in jurisdictions that are difficult to access or monitor. In the absence of a clear criminal offense, authorities are limited to an advisory or mediating role.

Meanwhile, Xavier is documenting every communication and compiling details in hopes of painting a broader picture. He denounces what he calls institutional silence, which he equates to abandonment. His mother has severed most ties; she missed her granddaughter’s wedding and didn’t even send Christmas greetings. Emotionally painful signs, but legally insignificant.

“I’m in love, I’m an adult, I have the right to be happy.”

Consular responses appear equally pragmatic: “When the money runs out, she’ll show up at the embassy,” was reportedly the remark of one official. A stark reality, but one that reflects standard operating procedure in regions beyond European jurisdiction.

In conclusion, Marie-José’s case is not an anomaly—it’s a symptom. A symptom of a sociocultural shift in which cross-border relationships, including in later life, are becoming more common. In this evolving landscape, the boundary between freedom and exploitation, love and self-interest, remains elusive. And in that grey area, neither law nor diplomacy currently has the tools to respond effectively.